The Making of the Sound Effects

One of the most notable aspects of the franchise has to be those “fast and furious” sound effects. I wrote in another blog post (you can read it here ) as to how the engine sounds were done, but here’s an excerpt of an interview [Written by Tim Walston for Designing Sound] back in April of 2011. This article explains the tricks used to get some of the sounds of the action sequences. Creating unique fast and furious style sound effects took the work of many talented “foley” artists.

“Action movies are pure sonic playgrounds. The busier the scene, and crazier the action, the more opportunities we have with sound to enhance the experience for the audience. But with that opportunity comes the responsibility to clarify the action, and focus the audience’s attention. We want to thrill the moviegoers, not pummel them with audio. As sound professionals, it’s our job to bring to the mix all the elements we think are needed. A great mixer then sorts through the dialog, music and all the sound effects to find the perfect balance from moment to moment. The ultimate authority, in the end, is the director.

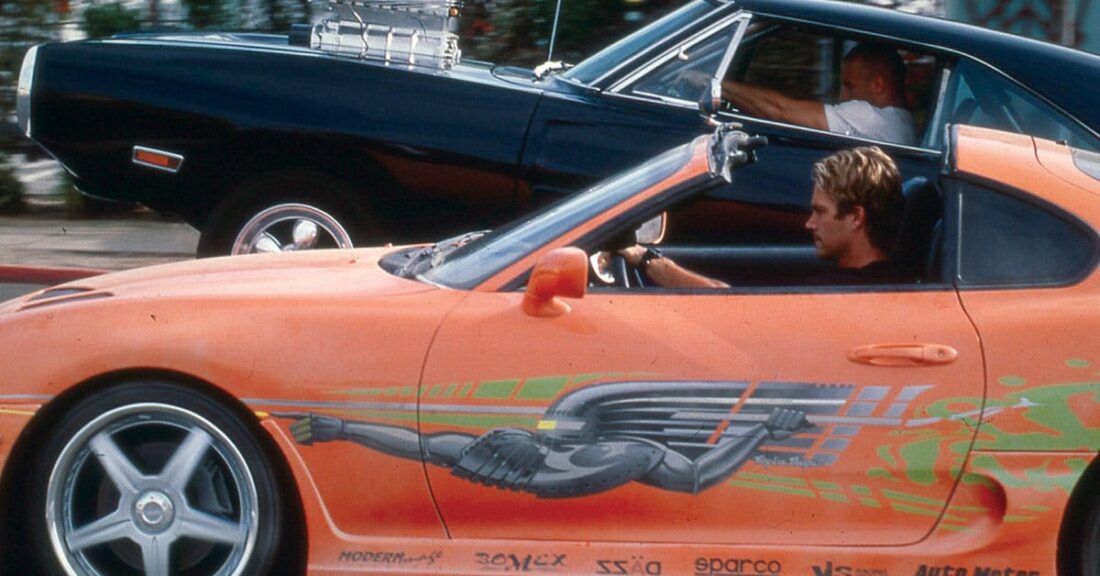

Rob Cohen makes movies that are great for sound. His action sequences are visceral, and visually dynamic. He also knows exactly what he wants sound to do for his films. I’ve had the good fortune to work on four of his films, and each one has been a blast.

The Fast and the Furious

I began work on “The Fast and the Furious” in 2000, while I was still the “new guy” at SoundStorm. It was one of my first big movies. It also marked the first time I worked on a multichannel surround speaker system. Although I was exploring new audio territory on a huge project, I knew the soundtrack itself was in good hands.

Supervising Sound Editor Bruce Stambler knows cars. He assembled a top-notch team of recordists and started recording extensive car libraries of a huge number of exotic cars. Every featured vehicle was researched and a suitable sound-alike was found. Recording sessions continued on throughout the post production process. I was not present at the recording sessions myself, but I heard the results and they were phenomenal.

All the cars were cut by SoundStorm editors using the Fostex Foundation 2000 system. Imagine having only 8 tracks available at one time! The interface consisted of a small touch screen. You can see more pictures of the system in this French article here – it even mentions SoundStorm and my mentor/predecessor Lance Brown if you scroll down to “Sound Design”.

My tasks on the show were primarily traditional “sound design” moments, and a few specialty sounds: CGI point-of-view shots flying inside of an engine, all the hi-tech NOS activations and associated power surges, some slow motion scenes, fast car by sweeteners, and most importantly: the “sense of speed”. We also planned for a layer of animal sweeteners ( a “sweetener” is any sound file that is laid into the soundtrack to “sweeten” the sound) for the cars. The sound design workload was already heavy, so we brought in Charles Deenen to take over that enormous task. He delivered spectacular tracks that added a new level of ferocity to the already outrageously aggressive car recordings.

We split up the sound design for predubs like this:

DSN A = Animal sweeteners, day-night transitions (Charles’ stuff)

DSN B = Design FX (NOS, titles, whooshes, etc.)

DSN C = Car sweeteners (multi-channel pre-panned bys, tires, engines)

DSN D = Int car wind & “sense of speed” FX

Each character was represented by a different set of design material. The unique sounds highlighted the different cars from shot to shot, to help the audience keep track of the characters. It also supported and reflected each person’s character traits.

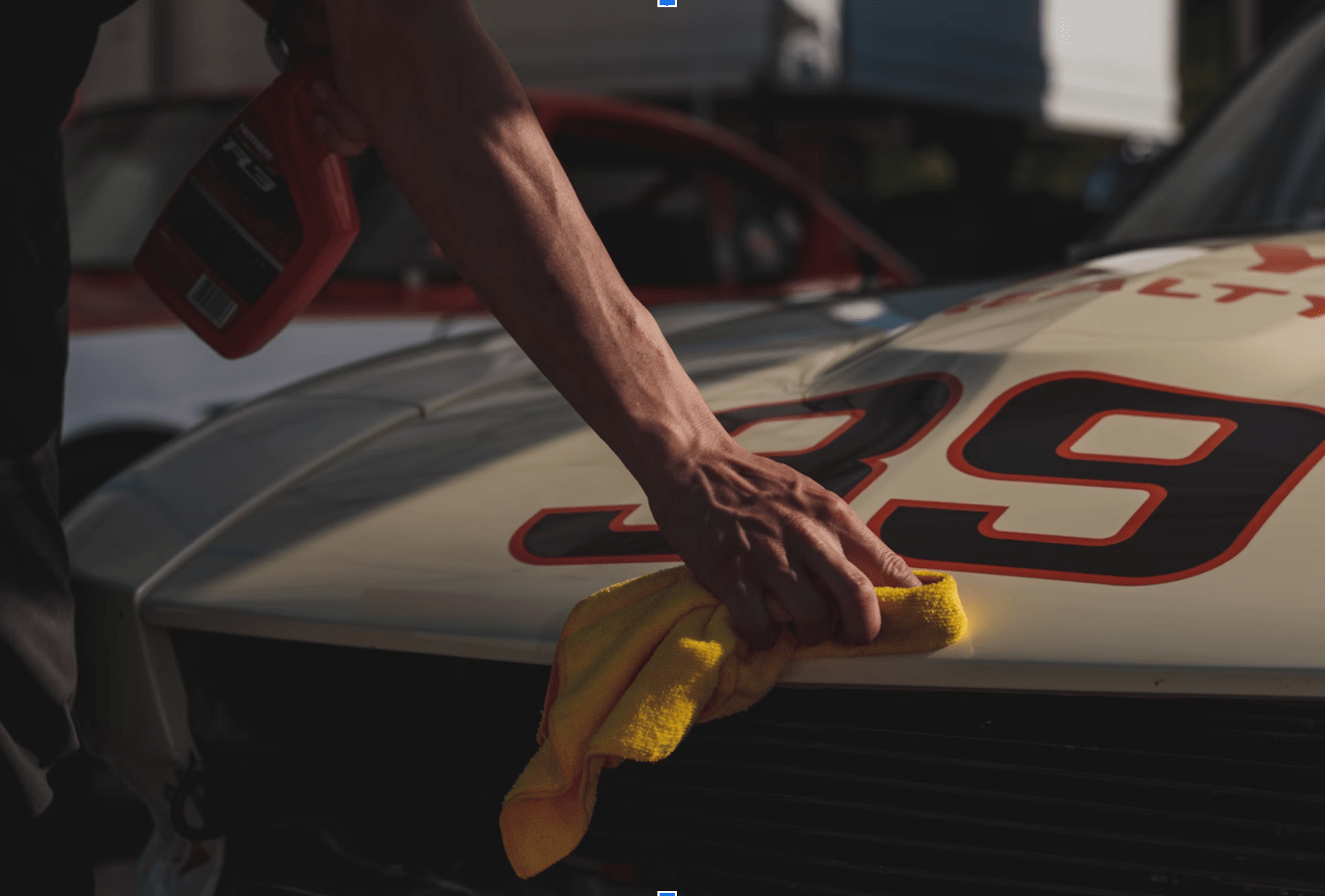

The NOS shots, like everything else in the movie, were larger-than-life events. The “inside the engine” shots were visually very dense. These all required very detailed work to convey such sonic complexity in a very short time. The best way I’ve found is to have little bits of sound follow each other in a sequence, instead of having too many sounds happening at one time. I think I spent about a week or so on the first 8 second trip through Dom’s engine. I used short pieces of evocative sounds: firey explosions, air blasts, spinning mechanical sounds. The cam shaft spins were created from an old slide projector sound effect. The “engine by” sound included a Close up engine recording of my old dead Buick Skyhawk on the day it was picked up for spare parts. It looked just like this one:

[I should note that I recorded another sound from this car that day… a sound that later became the Enterprise warp throttle down while the “parking brake” was on – but that’s another story.]

For the fast and furious sound effects, I kept going back to clarify the mix, and take advantage of the 5.1 speakers. For Temp (orary)1, I delivered my design as a virtual mixdown. I was pleased to get a call during the final mix to send my original Temp 1 mixdown to the stage, since they liked it so much. A year later I was pleasantly surprised to hear my entire “in the engine” sequence triggered from the DVD menu when the film is started.

The sense of speed was a fun challenge throughout the fast and furious project. During the high-octane race scenes, I wanted to create the feeling of dangerous acceleration. In nearly all those scenes, there are tonal sounds that rise in pitch and intensity – either low end moans or high end turbine-type sounds. Another key aspect was a set of various wind sounds. Everything from high whistley winds (also slowly rising in pitch) to monstrous low end buffeting roars were used. I also created some subjective sounds to convey the adrenaline rush felt by the drivers.

Last but not least, are what I called “blur bys”. I made a variety of aggressive and fast whoosh bys that I cut for foreground objects whizzing by. I panned the blur-bys and other design elements and rendered them using a third party panning plug-in. This was back in 2000, of course, so I was using version 5.0 of Pro Tools and surround panning had not yet been implemented at that time.

Brilliant, veteran mixer Dan Leahy mixed all the effects and design tracks. It was the first of many inspiring collaborations I’ve had with Dan. He brings incredible skill and enthusiasm to his projects in equal measure. At this point I want to stress again the team nature of the collaborative endeavor that is film sound. The sound crew for FATF included:

- Sound Design and Supervision: Bruce Stambler M.P.S.E., Jay Nierenberg M.P.S.E.

- Re-Recording Mixers: Michael Casper, Daniel J. Leahy

- Supervising ADR Editor: Becky Sullivan, M.P.S.E

- Sound Effects Editors: Steve Mann, M.P.S.E., Kim Secrist, Steven F. Nelson, Brian Best, Howard S.M. Neiman, Glenn Hoskinson

- Sound Design: Tim Walston, Charles Deenen

- Dialogue Editors: Mildred Iatrou Morgan, Robert Troy, Bill Dotson, Donald Warner, Jr., M.P.S.E., Cathy Speakman, Paul Curtis, John C. Stuver, M.P.S.E.

- ADR Editors: Nicholas Korda, Lee Lemont

- Supervising Foley Editor: Michael Dressel

- Foley Editors: Scott Curtis, Dan Yale

- Additional Effects Recording: Richard Yawn, M.P.S.E., Gary Blufer

- First Assistant Sound Editor: Paul Aulicino, M.P.S.E.

- Assistant ADR Editor: Marc Deschaine

- Assistant Sound Editors: Bradley Clouse, Bruce barris, Bill Cawley

- ADR Mixer: Jeff Gomillion

- Mixing Recordists: Charles Ajar, Jr., Andy Peach, Eric Justen

- Foley Mixers: Eric Thompson, C.A.S., Shawn Kennelly

- Foley Artists: Gregg Barbanell, Laura Macias, Sean Rowe”

END OF ARTICLE

Let me just add that the exact methods used to create sound effects are usually closely guarded secrets. That’s because Sound Design professionals are indeed artists and like magicians, they keep their tricks to themselves.

Here’s a great video about how the art of “foley” works.